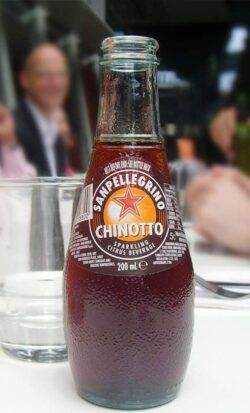

When I first saw the word Chinotto on a soda bottle in Le Marche, I assumed it was just a local soft drink—one of those regional curiosities Italy excels at. In truth, this soda is viewed by many here as a vastly improved, more adult version of Coca-Cola. I’m not a Coke fan, so comparisons are tricky, but Chinotto has a far more interesting profile: herbaceous, bitter-orange, and without the overly sweet jolt that Coke acquired after its clever bait-and-switch in the 1980s.

in Le Marche, I assumed it was just a local soft drink—one of those regional curiosities Italy excels at. In truth, this soda is viewed by many here as a vastly improved, more adult version of Coca-Cola. I’m not a Coke fan, so comparisons are tricky, but Chinotto has a far more interesting profile: herbaceous, bitter-orange, and without the overly sweet jolt that Coke acquired after its clever bait-and-switch in the 1980s.

My long-held suspicion is that the Coca-Cola overlords quietly and slowly swapped out cane sugar for corn syrup in the U.S in the mid ’80s. They then introduced a “new Coke” which was predictably booed out of the stadium and returned, with much corporate fanfare, to the “old Coke” recipe with corn syrup. (The production of corn syrup and its insidious use in the US is worthy of another post.) Everyone was so thrilled that the “real Coke” was back, no one made a fuss over the switcharoo. Only outside the U.S. does Coke still contain beet or cane sugar. That’s why “Mexican Coca-Cola” gets its own shelf talker in American eateries. But I’m wandering again—

What I didn’t know at first is that Chinotto is actually the fruit itself—a tiny, intensely aromatic citrus, Citrus myrtifolia, nicknamed “myrtle-leaf orange” because the foliage resembles myrtle. One of its advantages is that the branches carry no thorns, which for citrus pickers is already a hallelujah. It has powerfully fragrant blossoms and produces abundant clusters of these bittersweet miniature oranges. In fact, it is thought to be a mutation of the larger bitter orange and not an original species. The Chinotto arrived in Italy sometime in the 16th century, most likely from China, and today you can find orchards in Liguria, Sicily, Calabria, and Tuscany. They are decidedly not an eating orange: they are bitter, sour, and reputed to have a slight numbing effect on your mouth—which does not stop Italians from turning them into all manner of delights, from soft drinks to cocktails, candied peel to marmalades – and even digestive lozenges. I was surprised to learn that Chinotto oranges are also cultivated commercially now in California.

Bitter Lovers Unite

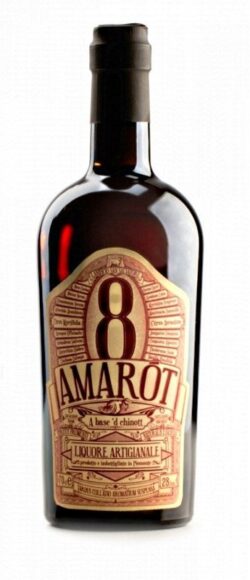

In Italy—where I’ve clearly found my tribe in the Fellowship of Bitter Flavor—Chinotto is used not only in marmalades (great accessory to a cheese plate) but also in some of the country’s prized amari. Bitter lives quite comfortably here, right alongside sweet. Even the most mundane grocery store stocks 70–90% cocoa chocolate bars. You may receive a single square of austere dark chocolate next to your thimble of espresso at a fine restaurant. And think of the vegetables Italians celebrate: puntarelle, cicoria, radicchio. Even Parmigiano, the King of Cheese, has its sharp edge of bitterness. And of course, Italian coffee—those tiny cups of ambrosial bitterness. (The RWM and I always joke that we came to Italy for the coffee but stayed for the grandsons.)

in marmalades (great accessory to a cheese plate) but also in some of the country’s prized amari. Bitter lives quite comfortably here, right alongside sweet. Even the most mundane grocery store stocks 70–90% cocoa chocolate bars. You may receive a single square of austere dark chocolate next to your thimble of espresso at a fine restaurant. And think of the vegetables Italians celebrate: puntarelle, cicoria, radicchio. Even Parmigiano, the King of Cheese, has its sharp edge of bitterness. And of course, Italian coffee—those tiny cups of ambrosial bitterness. (The RWM and I always joke that we came to Italy for the coffee but stayed for the grandsons.)

Still available, and wildly popular in the Belle Epoque, are candied Chinotto oranges in Maraschino liqueur. While syrups and jams are made with Chinotto, it may be most famous today as a flavoring agent in several amari, those after-dinner liqueurs that allegedly help your digestion. They certainly help mine. Campari is the best-known Chinotto-inflected brand, but if you can find Amaròt, try it. It is divine.

Still available, and wildly popular in the Belle Epoque, are candied Chinotto oranges in Maraschino liqueur. While syrups and jams are made with Chinotto, it may be most famous today as a flavoring agent in several amari, those after-dinner liqueurs that allegedly help your digestion. They certainly help mine. Campari is the best-known Chinotto-inflected brand, but if you can find Amaròt, try it. It is divine.

Chinotto has recently been added to the Slow Food Presidium, with the Chinotto di Savona being especially prized for its almost total lack of seeds. Other varieties include boxwood-leaf, crinkle-leaf, and a couple of dwarfs. Should I ever acquire my dream apartment in Bologna—with an actual balcony instead of a theoretical one—I may be unable to resist growing a Chinotto tree. They are quite comfortable in confined spaces. And as further natural decor, the oranges, first green, then gradually orange, remain on the branches for most of the year. When ripe, they are useful in your cooking – treat the fruit just as you would lemon or lime, for everything from marinades to desserts.

Having now fallen down the Chinotto rabbit hole (or thicket), I’m determined to find some at the Bologna markets this winter. I want to candy the peel and make a syrup from the whole fruit. I have been told that it is the not-so-secret ingredient in some famous Milan Negronis. This December plan comes—fairly shamelessly swiped—from a restaurant in Hackney, London, with the excellent name LARDO. I will absolutely have to go.

Chinotto Syrup

2025-12-08 19:07:31

- 1 kilo (2.2lbs) Chinotto Oranges

- 3 cups white granulated sugar - demerara or turbinado can be substituted but not the darker Muscovado sugars

- a selection of the following herbs and spices: rosemary, cardamom seeds, black peppercorns, whole cloves, stick cinnamon, mustard seeds, juniper berries

- Don't use too many cloves or you will end up with clove syrup.

- Make your syrup by combining the sugar and the water in a saucepan and allow it to boil just until the syrup becomes clear, then allow it to cool while you proceed with the fruit.

- Preheat the oven to 320F (160C)

- Cut the oranges in 1/2 inch(1 1/4cm) wedges - you want peel and seeds too.

- Line a sheet pan with parchment paper and scatter the orange wedges across the whole sheet.

- Sprinkle your selection of herbs and spices on top - remember that when the syrup is finished and marinating in your fridge, the taste of the spices gets stronger.

- Bake until the oranges start to char on the peel - it may take an hour or more.

- Transfer the wedges and their spices to a clean wide-mouthed glass jar.

- Pour the cooled syrup over them, stopping just below the neck.

- Weight the fruit down with a small object (an espresso saucer works perfectly) so everything stays submerged.

- Seal the jar and refrigerate for a week. The longer it rests, the more herbal and spicy the syrup becomes.

- The syrup can be used to flavor soda water, (a tablespoon per 8oz glass is suggested)

- You can create your own cocktails with this syrup as well, and certainly add a bit to a sauce for a pork roast, duck or game bird.

- You can use the syrup as part of a basting sauce for pork or poultry.

Adapted from Lardo Restaurant

Adapted from Lardo Restaurant

Kitchen Detail https://lacuisineus.com/

Comments are closed here.

Follow this link to create a Kitchen Detail account so that you can leave comments!