Read Time: 5 Minutes Subscribe & Share

A Warning

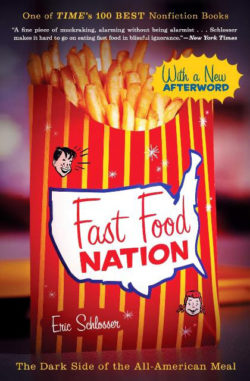

Fast Food Nation, published in 2001, was one of the first books we carried in the shop that dealt with food as a social and health issue. Previously, we sold mostly cookbooks and food memoirs. The book underlined what my husband and I had slowly begun to suspect — that food choices in the US were headed in a bad direction. After all, we took our oldest daughter to a McDonalds on Duke Street in Alexandria when she was tiny (sort of an American rite of passage – oh look, she’s feeding herself!) so that she could have her very own Big Mac. I grew up with the likes of Sir Loiner and Dairy Queen. I knew the delight of sighting Howard Johnson’s orange roof on road trips, promising a nice meal with delicious ice cream at the end. This evolving form of roadside dining seemed somewhat benign and a unique part of my American heritage. Reading through Schlosser’s book provided a well documented wake-up call.

Street in Alexandria when she was tiny (sort of an American rite of passage – oh look, she’s feeding herself!) so that she could have her very own Big Mac. I grew up with the likes of Sir Loiner and Dairy Queen. I knew the delight of sighting Howard Johnson’s orange roof on road trips, promising a nice meal with delicious ice cream at the end. This evolving form of roadside dining seemed somewhat benign and a unique part of my American heritage. Reading through Schlosser’s book provided a well documented wake-up call.

When It’s Not A Choice

We were fortunate that fast food was an optional occasional guilty pleasure. For far too many people, it is the only available way to feed a family that has limited resources and access. We have upset a crucial balance of healthy choices (grocery stores vs fast food spots). It becomes apparent when you witness the dearth of grocery options and the prevalence of roadside dining spots dotting the countryside when you venture beyond the comforts of your own neighborhood. I actually started to count fast food restaurants vs grocery stores when we went on trips in the US. Along one very bleak stretch on our way to the beach, I counted close to twenty fast food spots before finding a huge Walmart replete with an even larger steamingly hot parking lot. And even in Washington DC, you could drive for blocks in certain areas where there were only similar franchises but no food markets. These areas, whether rural or urban, are bereft of reasonable access to fresh foods. And their populations are paying the price in obesity, heart disease and diabetes. Although the term “food desert” is a recent one – first coined in 1995 by the Scottish Nutrition Task Force – the phenomenon has a long and unique history in the US.

We were fortunate that fast food was an optional occasional guilty pleasure. For far too many people, it is the only available way to feed a family that has limited resources and access. We have upset a crucial balance of healthy choices (grocery stores vs fast food spots). It becomes apparent when you witness the dearth of grocery options and the prevalence of roadside dining spots dotting the countryside when you venture beyond the comforts of your own neighborhood. I actually started to count fast food restaurants vs grocery stores when we went on trips in the US. Along one very bleak stretch on our way to the beach, I counted close to twenty fast food spots before finding a huge Walmart replete with an even larger steamingly hot parking lot. And even in Washington DC, you could drive for blocks in certain areas where there were only similar franchises but no food markets. These areas, whether rural or urban, are bereft of reasonable access to fresh foods. And their populations are paying the price in obesity, heart disease and diabetes. Although the term “food desert” is a recent one – first coined in 1995 by the Scottish Nutrition Task Force – the phenomenon has a long and unique history in the US.

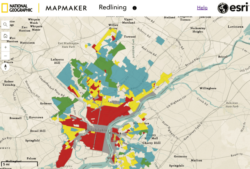

Code Red

According to Sentient Media, starting in the 1930s through the post WWII era, a “Second Migration” occurred, when African Americans escaping from the Jim Crow laws of the southern states moved to cities in the north and west. In response to a racially motivated fear by white residents that real estate values would go down, the Federal Housing Administration, through its agency, the Homeowners Land Corporation, created maps of neighborhoods that real estate companies and bank loan officers used when evaluating home sales prices and issuing home mortgages. Four colors (coded A,B,C,D) from green for “best”, blue for “still desirable”, yellow for “declining” and red for “hazardous”, were used in these nationally distributed maps. Reams of typewritten notes clarifying the designations make for appalling reading. The use of “redlining” as it was called was also put into play by the growing number of supermarkets, which would expand only into A and B areas. This left vast swaths across the US in which an exploding number of fast food restaurants could expand at a low cost – with nary a grocery store in sight. According to the NIS Library of Medicine Archives, in 2009, the USDA started mapping food access and reported later that:

According to Sentient Media, starting in the 1930s through the post WWII era, a “Second Migration” occurred, when African Americans escaping from the Jim Crow laws of the southern states moved to cities in the north and west. In response to a racially motivated fear by white residents that real estate values would go down, the Federal Housing Administration, through its agency, the Homeowners Land Corporation, created maps of neighborhoods that real estate companies and bank loan officers used when evaluating home sales prices and issuing home mortgages. Four colors (coded A,B,C,D) from green for “best”, blue for “still desirable”, yellow for “declining” and red for “hazardous”, were used in these nationally distributed maps. Reams of typewritten notes clarifying the designations make for appalling reading. The use of “redlining” as it was called was also put into play by the growing number of supermarkets, which would expand only into A and B areas. This left vast swaths across the US in which an exploding number of fast food restaurants could expand at a low cost – with nary a grocery store in sight. According to the NIS Library of Medicine Archives, in 2009, the USDA started mapping food access and reported later that:

food deserts exist in every American state, in all types of communities. It is estimated that roughly 23 million people lived in 6 529 food-desert communities. The USDA’s research elicited increased recognition of the vital role of people’s environment in supporting health and reducing disparities.

Help Is On the Way

Recognition of the problem that highly processed foods with low pricing (maintained in part by subsidies paid for with our tax dollars) has actually paved the way for some national and state approaches that, while seemingly small, are effectively addressing the food deserts in baby steps. In the first decade of the 21st century, Federal and state funds together created the Healthy Food Financing Initiative (HFFI) which has turned out to be a pretty effective and economically sustainable solution. HFFI programs provide one-time grants and loans to projects seeking to improve access to healthy foods by financing grocery stores, farmers’ markets, food hubs, co-ops and other food access businesses in urban or rural areas of need. My husband remembers Ralph Sampson – a basketball great who went to the University of Virginia – now he is using HFFI funds to restore his family farm as a sustainable agricultural training enterprise. You can read through their programs to see how they have grown their leverage by partnering with local businesses here.

subsidies paid for with our tax dollars) has actually paved the way for some national and state approaches that, while seemingly small, are effectively addressing the food deserts in baby steps. In the first decade of the 21st century, Federal and state funds together created the Healthy Food Financing Initiative (HFFI) which has turned out to be a pretty effective and economically sustainable solution. HFFI programs provide one-time grants and loans to projects seeking to improve access to healthy foods by financing grocery stores, farmers’ markets, food hubs, co-ops and other food access businesses in urban or rural areas of need. My husband remembers Ralph Sampson – a basketball great who went to the University of Virginia – now he is using HFFI funds to restore his family farm as a sustainable agricultural training enterprise. You can read through their programs to see how they have grown their leverage by partnering with local businesses here.

So encouraging.

Other campaigns are generated by groups of individuals and farming organizations. It’s been reassuring to read about one in my former home – The Arcadia Center for Sustainable Food and Agriculture, which works in partnership with the National Trust for Historic Preservation as part of the Woodlawn Estate. Arcadia tackles food deserts from the ground up — beginning with growing food on its four-acre farm and children’s garden to stock farmers’ markets, on through teaching people how to be farmers, and helping community residents learn about being nutritionally literate consumers.

Other campaigns are generated by groups of individuals and farming organizations. It’s been reassuring to read about one in my former home – The Arcadia Center for Sustainable Food and Agriculture, which works in partnership with the National Trust for Historic Preservation as part of the Woodlawn Estate. Arcadia tackles food deserts from the ground up — beginning with growing food on its four-acre farm and children’s garden to stock farmers’ markets, on through teaching people how to be farmers, and helping community residents learn about being nutritionally literate consumers.

Our sharp-penciled editor has been part of a happy volunteer army at Arcadia for three seasons, planting, weeding, harvesting and tasting the fruits of their labor. Volunteering on a community farm or farmer’s market, she says, is a glorious way to counteract life’s tensions and help make sure that everyone can “get their hands on delicious, affordable, local food,” as Arcadia’s website explains its mission. An antidote for what ails the world, and a marvelous way to fulfill student volunteer service hours, said last week’s high school seniors as they turned and sifted compost.

Another example would be the Urban Forest at Browns Mill in Atlanta. Georgia. It is an example of utilizing abandoned land or city-owned plots in urban spaces for community-sustained agriculture. With the help of the city government and federal or state funding, licensing, insurance, technical assistance are provided with the goal of making fresh produce (and occasionally eggs and meats) available to residents in what were termed Food Deserts. In the Aglanta program– abandoned lots are up for community adoption to create Food Forests. These individual programs, though tiny, aim to provide unprocessed food for residents within a half mile. They also bring biodiversity, soil rehabilitation, and climate change mitigation.

Georgia. It is an example of utilizing abandoned land or city-owned plots in urban spaces for community-sustained agriculture. With the help of the city government and federal or state funding, licensing, insurance, technical assistance are provided with the goal of making fresh produce (and occasionally eggs and meats) available to residents in what were termed Food Deserts. In the Aglanta program– abandoned lots are up for community adoption to create Food Forests. These individual programs, though tiny, aim to provide unprocessed food for residents within a half mile. They also bring biodiversity, soil rehabilitation, and climate change mitigation.

It makes my heart sing.

Kitchen Detail shares under the radar recipes, explores the art of cooking, the stories behind food, and the tools that bring it all together, while uncovering the social, political, and environmental truths that shape our culinary world.

Comments are closed here.

Follow this link to create a Kitchen Detail account so that you can leave comments!