Read Time: 5 Minutes Subscribe & Share

A Feast Of A Film

When I wrote about Mapie de Toulouse-Lautrec in the previous post, it struck me that I should write about her much more famous in-law, the painter, who was also quite a cook. He was one of the first artists I remember admiring as a tween. I had dreams of becoming a broadway dancer, and loved the music of Offenbach and of course the Can-Can — so much so that my father personally escorted me to see the film Moulin Rouge, not the one you are thinking of by Baz Luhrmann but rather the one directed by John Huston in 1952. Surprisingly, in this 73-year-old biofilm, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and the characters that make up both his art and his life walk right out of his drawings and paintings. José Ferrar is remarkable as the crippled painter. To play the role, he walked on his knees with his lower limbs strapped to his upper body, using knee pads of his own design for this painful role. N.B. he also played the role of the painter’s unforgiving and absent father in the film. You will enjoy watching it on Netflix.

When I wrote about Mapie de Toulouse-Lautrec in the previous post, it struck me that I should write about her much more famous in-law, the painter, who was also quite a cook. He was one of the first artists I remember admiring as a tween. I had dreams of becoming a broadway dancer, and loved the music of Offenbach and of course the Can-Can — so much so that my father personally escorted me to see the film Moulin Rouge, not the one you are thinking of by Baz Luhrmann but rather the one directed by John Huston in 1952. Surprisingly, in this 73-year-old biofilm, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and the characters that make up both his art and his life walk right out of his drawings and paintings. José Ferrar is remarkable as the crippled painter. To play the role, he walked on his knees with his lower limbs strapped to his upper body, using knee pads of his own design for this painful role. N.B. he also played the role of the painter’s unforgiving and absent father in the film. You will enjoy watching it on Netflix.

Cooking As An Art Form

To briefly recap, Henri, his legs stunted from falls and a genetic disorder, forsakes a rich aristocratic life near Albi, France in which he can truly play no part. The Toulouse-Lautrec family was noted for its hectic pursuit of all things sport and hunting. Forced to lie in bed for various failed operations, Henri turned to drawing and benefitted from his mother’s love of cooking and planning menus for a country estate where game and fish were plentiful. She, as a devout Catholic, separated from but never divorced her philandering husband, and even moved to Paris for a time with Henri when he was a child. At the age of 18, he permanently moved to Paris to study painting. His move was timed at the height of La Belle Epoque, when Paris was a freewheeling epicenter of industrial and artistic innovation and his neighborhood of Montmartre devolved into a hotbed of laborers, artists and sex workers.

While I had chucked my copy of Mapie’s cookbook, I always kept L’Art de la Cuisine, coauthored in a sense by Henri and his lifelong friend Maurice Joyant. It currently resides in one of the 106 boxes of our goods stored in Milan. I do remember that I had once made his lemon tart with some adjustments. My hazy recollection is that it was intense in texture and quite tasty. The recipe, like the others in the book, is pretty terse in its instructions. I think I will try to make it again with the fabulous lemons I see in the Bologna markets.

While I had chucked my copy of Mapie’s cookbook, I always kept L’Art de la Cuisine, coauthored in a sense by Henri and his lifelong friend Maurice Joyant. It currently resides in one of the 106 boxes of our goods stored in Milan. I do remember that I had once made his lemon tart with some adjustments. My hazy recollection is that it was intense in texture and quite tasty. The recipe, like the others in the book, is pretty terse in its instructions. I think I will try to make it again with the fabulous lemons I see in the Bologna markets.

Lay some tart pastry in an open pie dish, covering the sides. Lay over it the following mixture: beat three whole eggs as for an omelette. Add their weight in granulated sugar and juice of a lemon and its grated zest. Add seventy grams of butter cut into small pieces. Put into a moderate oven.

The American version had the help of Barbara Kafka, a noted food writer and recipe fixer, who wrote “3/4 cup sugar, ⅓ cup butter 375F oven for 20 minutes.” The filling fit a 20cm or less (8 or 7 inch) shallow tart pan. With a hand mixer I whipped the sugar and eggs together (and I did weigh out the eggs in the shell and then used the same weight in sugar). The lemon juice and zest were folded in after I had beaten the butter into the mixture.

A Posthumous Recipe Collection

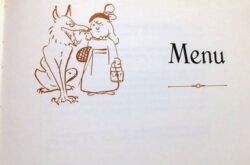

- The cookbook has some of the most charming drawings that one does not normally find in coffee table

art books. The artist would draw his own invitations for dinners and also his menus. My favorite is the little girl with the wolf, which adorned one of his menus. Maurice Joyant, who was his cooking buddy, close friend and art dealer, culled the recipes, drawings and texts that Henri had written as a posthumous homage to the painter. It includes recipes that they made together, some purely fantasy and even a satirical recipe for grilling grasshoppers like Saint John The Baptist. They suggested that “should you want to grill a Saint, with the help of the Vatican, try to procure for yourself a real saint.”

art books. The artist would draw his own invitations for dinners and also his menus. My favorite is the little girl with the wolf, which adorned one of his menus. Maurice Joyant, who was his cooking buddy, close friend and art dealer, culled the recipes, drawings and texts that Henri had written as a posthumous homage to the painter. It includes recipes that they made together, some purely fantasy and even a satirical recipe for grilling grasshoppers like Saint John The Baptist. They suggested that “should you want to grill a Saint, with the help of the Vatican, try to procure for yourself a real saint.”

Henri’s mother would visit him almost weekly, bringing with her a hamper of foods from her family’s estate, and they cooked and planned dinners at both his studio and at friends’ homes. And what adventurous meals they were, with the likes of lobster A L’Americaine (his favorite), seven-hour leg of lamb – and stewed turbot livers, along with heart-stopping cocktails such as his Earthquake – which was equal parts cognac and absinthe.

Henri usually carried a whole nutmeg and a tiny grater that he used to flavor port wine, which he drank in prodigious amounts. In the film, Huston truthfully portrayed him with his hollowed cane in which he kept alcohol – he drank from the handle and regularly refilled the cane. Once, when drinking milk in the afternoon became a “thing” in Paris, a friend asked him to at least make a switch from alcohol during that period. Henri responded that he would drink milk when cows ate grapes. He died at the age of 36 of syphilis and alcoholism, leaving behind a legacy of making posters as an art form, affectionate drawings and paintings of a working class world that had previously been ignored. While I probably will not cook a marmot as he suggests, I do want to try his wild pigeon with olives.

Henri usually carried a whole nutmeg and a tiny grater that he used to flavor port wine, which he drank in prodigious amounts. In the film, Huston truthfully portrayed him with his hollowed cane in which he kept alcohol – he drank from the handle and regularly refilled the cane. Once, when drinking milk in the afternoon became a “thing” in Paris, a friend asked him to at least make a switch from alcohol during that period. Henri responded that he would drink milk when cows ate grapes. He died at the age of 36 of syphilis and alcoholism, leaving behind a legacy of making posters as an art form, affectionate drawings and paintings of a working class world that had previously been ignored. While I probably will not cook a marmot as he suggests, I do want to try his wild pigeon with olives.

Kitchen Detail shares under the radar recipes, explores the art of cooking, the stories behind food, and the tools that bring it all together, while uncovering the social, political, and environmental truths that shape our culinary world.

Comments are closed here.

Follow this link to create a Kitchen Detail account so that you can leave comments!