Read Time: 6 Minutes Subscribe & Share

Like Water Into Wine

Last week’s post about the Salad Goddess brought some requests from readers about ingredients, such as any mustard favorites, what types of vinegars, oils and what brands. This will not be the only discussion of these topics, but I want to start out with the subject of wine vinegars and my preference.

Last week’s post about the Salad Goddess brought some requests from readers about ingredients, such as any mustard favorites, what types of vinegars, oils and what brands. This will not be the only discussion of these topics, but I want to start out with the subject of wine vinegars and my preference.

One of the neatest aspects of attending the Fancy Food Shows was the ability to simply taste a broad range of suppliers of a particular ingredient, both domestic and foreign. We Cuisinettes always learned a lot. And it was often surprising to see what we agreed on and where our opinions diverged.

As an example, the Cuisinettes were all over the place on olive oils. In the end, we decided that we would look for unique and long-lasting flavors of olive oils in terms of regions. But one of the areas we all agreed on was that for wine vinegars, Martin Pouret was the best choice, based on our NASFT tastings.

Of course there are other types of vinegars, and I will write about my exploration of those in another post. Basically, vinegar is the end-product of a chemical reaction that occurs when a particular bacterium (Acetobacter aceti) comes into contact with alcohol, and the former turns the latter to acetic acid and water. It is the character and treatment of the alcohol that has turned acidic that provides vinegar’s unique taste and quality.

Wine, Temperature & Time

You can thank Louis Pasteur for several discoveries, one of them being to ascertain and put a scientific name to the bacterium — Acetobacter aceti — that can work with warm air to turn the alcohol in wine into acetic acid. This discovery, according to William Grimes who wrote an nsightful article in the New York Times: “helped make industrial production of vinegar possible. Today, by raising the temperature of wine and speeding up the fermentation, producers can turn out thousands of gallons of vinegar in 24 hours from giant steel tanks.” But that is not the process at Martin Pouret.

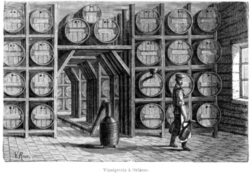

The initial acetification of a Pouret wine vinegar takes about a month and then, depending on the style of vinegar desired, the acetified wines are aged in oak barrels for several months before filtering and bottling. Each barrel is filled only to 75% capacity, as oxygen is needed for the bacteria to further develop the vinegar. The wine is never heated as is required in the industrial process, as that kills off its flavor. In a three-week period, a third of the wine is removed and new wine is poured in to replace. William Grimes also noted that after three weeks, no more beneficial acetification occurs. Flavorings such as tarragon are added just before bottling.

acetified wines are aged in oak barrels for several months before filtering and bottling. Each barrel is filled only to 75% capacity, as oxygen is needed for the bacteria to further develop the vinegar. The wine is never heated as is required in the industrial process, as that kills off its flavor. In a three-week period, a third of the wine is removed and new wine is poured in to replace. William Grimes also noted that after three weeks, no more beneficial acetification occurs. Flavorings such as tarragon are added just before bottling.

Balancing Act

Creating a balanced wine vinegar is more than simply taking leftover wine and acetifying it with a “mother” or relying on heat to speedily activate the bacterium. Martin Pouret vinegars are so much better than their industrially produced competitors, or even homemade efforts. My own brief experience at making wine vinegar proved to be quite unpredictable, and several bottles of industrial wine vinegar I purchased had a sharp unpleasant taste that was hard to overcome in a sauce or dressing. But the Martin Pouret vinegars never disappoint. Interestingly, their vinegars have a 7% acidity, while many of their industrial competitors have a lesser percentage. It is that higher level of acidity, along with their choice of unheated wines, careful aging and fermentation control that give this company’s selections an edge over the competition.

Creating a balanced wine vinegar is more than simply taking leftover wine and acetifying it with a “mother” or relying on heat to speedily activate the bacterium. Martin Pouret vinegars are so much better than their industrially produced competitors, or even homemade efforts. My own brief experience at making wine vinegar proved to be quite unpredictable, and several bottles of industrial wine vinegar I purchased had a sharp unpleasant taste that was hard to overcome in a sauce or dressing. But the Martin Pouret vinegars never disappoint. Interestingly, their vinegars have a 7% acidity, while many of their industrial competitors have a lesser percentage. It is that higher level of acidity, along with their choice of unheated wines, careful aging and fermentation control that give this company’s selections an edge over the competition.

Transport Creates A Product

Orleans, France developed into a prominent port city beginning in the Middle Ages, with its access to canals and sitting on the Loire River. Canals from the Loire created a network of shipping routes all the way to the Mediterranean Sea in the south and to the Atlantic Ocean in the north. When you consider that all products were shipped domestically via barge on a system of canals connecting to rivers in France, it would make sense that the storied wines of Bordeaux would have to travel to Paris on the same water routes. In that lengthy and non-temperature-controlled journey, wines would go bad and be off-loaded in Orleans.

Orleans, France developed into a prominent port city beginning in the Middle Ages, with its access to canals and sitting on the Loire River. Canals from the Loire created a network of shipping routes all the way to the Mediterranean Sea in the south and to the Atlantic Ocean in the north. When you consider that all products were shipped domestically via barge on a system of canals connecting to rivers in France, it would make sense that the storied wines of Bordeaux would have to travel to Paris on the same water routes. In that lengthy and non-temperature-controlled journey, wines would go bad and be off-loaded in Orleans.

In a classic waste-not-want-not progression, entrepreneurs in Orleans had by the beginning of the 15th century established a guild of “vinaigriers, buffetiers, sauciers et moutardiers d’Orléans”. Orleans became host to about 200-300 vinegar production houses, and the codifying and patenting of the production of wine vinegars was registered in 1597. The firm of Pouret was established in 1797 by a wine negociant with that last name. His first name is not known. As silting overtook canals and the network of railroads grew, the importance of Orleans as a port city faded. Louis Pasteur’s identification and processing of the bacterium that creates vinegar introduced a new way to produce large steel tanks of vinegar, and both the city and its method for producing wine vinegar faded into the past.

Not Just For Salads

It should be noted that vinegar was at one time used not just for sauces, but also as a medication, a boon to the proliferation of the Orleans vinegar houses – think Big Pharma in Olden Times. While its healing properties have long been scientifically examined and debunked, segments of our population still use apple cider vinegar in the belief that it can not only enhance athletic performance, but also act as a medication for kidney stones, diabetes and weight reduction (a popular affectation for women in English 18th and 19th century literature). Even during the 21st century Covid Pandemic, apple cider vinegar was a popular “preventative” against Covid 19, based on zero scientific evidence to support its use. It was also popular for preserving snuff, as long as the vinegar had enough floral scent to offset the pickling sensation in the nose of the user. And, as any reader of Jane Austen knows, “vinaigrettes” were vinegar-soaked sponges in artfully fabricated containers used by ladies to recover from fainting spells.

It should be noted that vinegar was at one time used not just for sauces, but also as a medication, a boon to the proliferation of the Orleans vinegar houses – think Big Pharma in Olden Times. While its healing properties have long been scientifically examined and debunked, segments of our population still use apple cider vinegar in the belief that it can not only enhance athletic performance, but also act as a medication for kidney stones, diabetes and weight reduction (a popular affectation for women in English 18th and 19th century literature). Even during the 21st century Covid Pandemic, apple cider vinegar was a popular “preventative” against Covid 19, based on zero scientific evidence to support its use. It was also popular for preserving snuff, as long as the vinegar had enough floral scent to offset the pickling sensation in the nose of the user. And, as any reader of Jane Austen knows, “vinaigrettes” were vinegar-soaked sponges in artfully fabricated containers used by ladies to recover from fainting spells.

Martin Pouret Today

Martin was added to the Pouret name as Martin-Pouret after Jeanne Pouret married Robert Martin in 1910. A grandson ran the company until 2019, when David Matheron and Paul-Olivier Claudepierre took over the management. Martin Pouret remains a very small company with fewer than fifty employees. The current team has rebranded and expanded the Martin Pouret repertoire of products, while still using traditional methods and recipes. And it shows.

2019, when David Matheron and Paul-Olivier Claudepierre took over the management. Martin Pouret remains a very small company with fewer than fifty employees. The current team has rebranded and expanded the Martin Pouret repertoire of products, while still using traditional methods and recipes. And it shows.

My favorite white vinegar for sauces and dressings is the Martin Pouret Champagne vinegar, and I purchase the large bottle of their red wine version as I use that more frequently. The other faves in my cupboard are the Raspberry White Wine Vinegar and another one flavored with tarragon leaves. The raspberry one I use to make a duck recipe that I learned from Jacqueline Panel of Chocolaterie Panel and for fruit-based salads. The tarragon version I use in chicken and fish dishes as well as potato salad. A good source for this company’s vinegars is Simply Gourmand which also carries the French flavoring essences we used to sell at La Cuisine. If you have not used your KD code WELCOME15% for a 15% discount on your first order, it is still available. Alternatively Simply Gourmand currently offers a 10% discount for people who sign up for their VIP text list.

Kitchen Detail shares under the radar recipes, explores the art of cooking, the stories behind food, and the tools that bring it all together, while uncovering the social, political, and environmental truths that shape our culinary world.

Comments are closed here.

Follow this link to create a Kitchen Detail account so that you can leave comments!