Read Time: 5 Minutes Subscribe & Share

A Good Deal

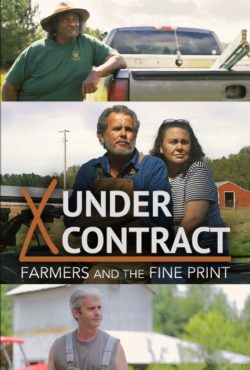

Some time ago, when my husband formed a small construction company, I visited a farm that belonged to the brother of one of his superintendents. He had recently entered into a contract to raise chickens for a large company as a way to make his small farm more profitable. He had paid for a large hangar-sized barn and was probably about two years into his leasing arrangement with what we now would call an industrial poultry corporation. He followed the protocols and every few weeks purchased the required feed and antibiotics to pass the state and federal regulations. Every few weeks company trucks would arrive, remove the surviving chickens and clean out the carcasses of the deceased ones. The ground inside the hangar barn was raked over and “cleaned.” A second set of trucks would arrive with patented chicks and the process would start over again. The brother was quite pleased with the contract, and it had indeed added income to his livelihood. I didn’t know what to expect, but entering into the barn was pretty much what Leah Garces of Mercy For Animals (a non-profit group that a promotes plant-based food system) saw in the second of three New York Times Opinion videos about the terrible state of our food system. I was not prepared.

belonged to the brother of one of his superintendents. He had recently entered into a contract to raise chickens for a large company as a way to make his small farm more profitable. He had paid for a large hangar-sized barn and was probably about two years into his leasing arrangement with what we now would call an industrial poultry corporation. He followed the protocols and every few weeks purchased the required feed and antibiotics to pass the state and federal regulations. Every few weeks company trucks would arrive, remove the surviving chickens and clean out the carcasses of the deceased ones. The ground inside the hangar barn was raked over and “cleaned.” A second set of trucks would arrive with patented chicks and the process would start over again. The brother was quite pleased with the contract, and it had indeed added income to his livelihood. I didn’t know what to expect, but entering into the barn was pretty much what Leah Garces of Mercy For Animals (a non-profit group that a promotes plant-based food system) saw in the second of three New York Times Opinion videos about the terrible state of our food system. I was not prepared.

Of the three Opinion videos, the second is perhaps the most difficult to digest. But if we consumers are to help push the wheel and outlaw the appalling aspects of the food we purchase, it is videos like this one that graphically showcase what we know is wrong, but often don’t act upon. We are paradoxically subsidizing the false premise of cheap poultry with our tax dollars.

How We Got Here

Chicken was not always a cheap food choice. Rather, a roasted chicken was showcased as an expensive treat to have on holidays. Most chickens were raised for eggs, and older ones, having lost their ability to lay, were relegated to stews. Rural families ordered eggs, which they would hatch to keep a steady flock of “layers”. A Delaware woman, Cecile Steele, had routinely placed an order for 50 fertilized eggs, but in a now famous delivery mistake, was shipped 500 of them. Determined to make the best of the surprise, she ordered a large chicken house from a Maryland lumberman, which is now on the historic register of Delaware. She was the first person to commercially raise chickens for meat in the DelMarVa peninsula. In her first foray, she sold 387 birds (each weighing under 3lbs) netting her 67 cents per

treat to have on holidays. Most chickens were raised for eggs, and older ones, having lost their ability to lay, were relegated to stews. Rural families ordered eggs, which they would hatch to keep a steady flock of “layers”. A Delaware woman, Cecile Steele, had routinely placed an order for 50 fertilized eggs, but in a now famous delivery mistake, was shipped 500 of them. Determined to make the best of the surprise, she ordered a large chicken house from a Maryland lumberman, which is now on the historic register of Delaware. She was the first person to commercially raise chickens for meat in the DelMarVa peninsula. In her first foray, she sold 387 birds (each weighing under 3lbs) netting her 67 cents per pound. For a poverty stricken rural family, this was an astounding financial windfall. The following year, she ordered 1000 eggs, and by 1926 she had developed a business that annually processed 10,000 chickens for meat. Other farms in the area, having suffered a peach and strawberry blight, soon followed suit. Even the now infamous Perdue Poultry (which had previously been a commercial egg farm) got their start from this deeply religious farm woman who clearly believed in the axiom of “waste not, want not”. Transportation and refrigeration in the roaring 20s had improved, and the first small chains of grocery stores appeared, so that a roast chicken for a Sunday dinner became a byword. One of the first big players was the A&P grocery store chain.

pound. For a poverty stricken rural family, this was an astounding financial windfall. The following year, she ordered 1000 eggs, and by 1926 she had developed a business that annually processed 10,000 chickens for meat. Other farms in the area, having suffered a peach and strawberry blight, soon followed suit. Even the now infamous Perdue Poultry (which had previously been a commercial egg farm) got their start from this deeply religious farm woman who clearly believed in the axiom of “waste not, want not”. Transportation and refrigeration in the roaring 20s had improved, and the first small chains of grocery stores appeared, so that a roast chicken for a Sunday dinner became a byword. One of the first big players was the A&P grocery store chain.

The Chicken Of Tomorrow

By the 1940s, a competition to raise fatter chickens arose, encouraged by both state and federal agencies . The USDA sponsored a contest with A&P, then the biggest grocery retailer. It was titled “The Chicken Of Tomorrow.” A fatter chicken with more meat in the right places to feed a family was seen as a progressive goal. The ultimate winner of this series of nationwide competitions was the Arbor Acres bird, by Frank Saglio of Glastonbury, Connecticut. Ultimately, his White Rock was bred with the Red Cornish by the Saglio family, and modified variants of this breed are still used globally in factory poultry farms. His winning chicken weighed just under 4lbs and was raised in less than 90 days. The standard now is under 6lbs in 46 days.

. The USDA sponsored a contest with A&P, then the biggest grocery retailer. It was titled “The Chicken Of Tomorrow.” A fatter chicken with more meat in the right places to feed a family was seen as a progressive goal. The ultimate winner of this series of nationwide competitions was the Arbor Acres bird, by Frank Saglio of Glastonbury, Connecticut. Ultimately, his White Rock was bred with the Red Cornish by the Saglio family, and modified variants of this breed are still used globally in factory poultry farms. His winning chicken weighed just under 4lbs and was raised in less than 90 days. The standard now is under 6lbs in 46 days.

The Farmer Of Today

According to The Guardian, over 97% of the chicken we eat is produced by farms under contract with “vertically integrated” corporations such as Tyson Foods, JBS and Perdue. Currently, farmers have to sign an exclusive contract, whose terms require taking out loans to purchase the housing, equipment, feed and antibiotics that the company specifies. In many cases, the company owns the “subsidiaries” that provide the housing, equipment, feed and antibiotics the farmers must purchase. These corporations also own the processing plants, which raises yet another barrier to independent poultry producers, but that is another story. Upgrades demanded by the corporation are often not included in the original contract. The farmland and buildings are collateral for the loans, so if their contract is forfeited, their homes and land are lost. The Corporations can retaliate against farmers who complain or rally for legal protection by giving them sick chickens. The number of dead chickens is deducted from what they would have received. Another slick operation is the “tournament system” described by the Guardian:

“vertically integrated” corporations such as Tyson Foods, JBS and Perdue. Currently, farmers have to sign an exclusive contract, whose terms require taking out loans to purchase the housing, equipment, feed and antibiotics that the company specifies. In many cases, the company owns the “subsidiaries” that provide the housing, equipment, feed and antibiotics the farmers must purchase. These corporations also own the processing plants, which raises yet another barrier to independent poultry producers, but that is another story. Upgrades demanded by the corporation are often not included in the original contract. The farmland and buildings are collateral for the loans, so if their contract is forfeited, their homes and land are lost. The Corporations can retaliate against farmers who complain or rally for legal protection by giving them sick chickens. The number of dead chickens is deducted from what they would have received. Another slick operation is the “tournament system” described by the Guardian:

The superintendent’s brother finally forfeited his contract with the poultry company (which had been swallowed by a larger one) or had it cancelled, after losing money with the increasing costs of following the protocols of his contract. Like so many others competing in the chicken tournament, he was out of the game.

Kitchen Detail shares under the radar recipes, explores the art of cooking, the stories behind food, and the tools that bring it all together, while uncovering the social, political, and environmental truths that shape our culinary world.

Comments are closed here.

Follow this link to create a Kitchen Detail account so that you can leave comments!