Read Time: 5 Minutes Subscribe & Share

Ciao Bella

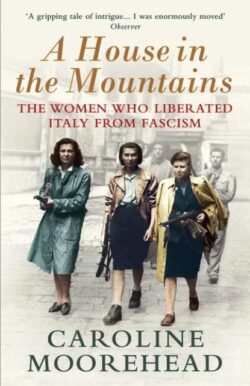

I am slowly finding my way to reading serious stuff once again. Bologna was a hotbed of partisan activity even before World War II broke out and its ranks were filled with women, so I have ordered A House In The Mountains, from Feltrinelli, a marvelous bookstore here. Caroline Moorhead’s highly regarded account is of a group of Italian Partigiani women who worked tirelessly against not only the occupying Nazi military but also their own Fascist government. After the end of World War II they were, of course, not given the recognition they deserved. This volume is one of four books Moorehead wrote as The Resistance Quartet. The others are A Train In Winter, A Bold And Dangerous Family and Village Of Secrets.

But this January, with weather forecasts clearly telling us that things are not meteorologically normal, I am trying to limit my doomsday reading. Instead, I am working on my Italian by reading a book on Amaro – a digestivo with promised medicinal values, which comes in an amazing number of regional varieties (a translated version is available in the US). In English, I am mid-course into an intriguing book about the origins and evolution of ten iconic pasta dishes of Italy.

Pasta Sleuth

The author is Luca Cesari, a culinary historian of Italian food who writes for Gambero Rosso plus other publications. He has also appeared on Italian TV and given numerous interviews. While The Discovery of Pasta is available in English, his second, La Storia Della Pizza – Da Napoli A Hollywood has not yet been translated in the US. A third volume is in the works, all about the cutlet across the globe. As someone who has searched for a proper Wiener Schnitzel for some time, (it ain’t easy to get right) I look forward to this as future post-Christmas reading – sort of like a reading futures account.

The author is Luca Cesari, a culinary historian of Italian food who writes for Gambero Rosso plus other publications. He has also appeared on Italian TV and given numerous interviews. While The Discovery of Pasta is available in English, his second, La Storia Della Pizza – Da Napoli A Hollywood has not yet been translated in the US. A third volume is in the works, all about the cutlet across the globe. As someone who has searched for a proper Wiener Schnitzel for some time, (it ain’t easy to get right) I look forward to this as future post-Christmas reading – sort of like a reading futures account.

Luca Cesari dashed my carefully researched KD post on Spaghetti Alla Carbonara. It turns out that the Bolognese chef Renato Gualandi did not in fact create a loaves and fishes dinner (albeit with the Allied rations of powdered eggs and bacon) for the top officers of the British and American military after the Allied victory. Apparently, in his biography written in 2006, Gualandi gave a detailed account of the dinner he actually served with nary a mention of spaghetti alla carbonara.

We served 3,000 petit fours, various pastries, raw crudités, assorted canapes with cheeses and meats, Then a soup of lettuce hearts and a classic Irish stew with lamb, mutton and vegetables. After that, a bone-in roast of beef covered in kidney fat, to be cut on the diagonal like salmon, with a savoury pudding and gravy. Last a cake a metre-and-a-half tall shaped like the two towers of Bologna. And then at the end of the dinner came a Welsh rarebit; cheddar cheese on toast with egg yolks, rum, salt and sugar, broiled in the oven and washed down with plenty of beer.

That said, Luca’s theory is that carbonara’s origins are murky and relatively new – the dish could be a combination of Italian inventiveness along with bacon and eggs with origins in post-war Rome. He has a copy of Cucina Italiana with a 1954 recipe for spaghetti carbonara with gruyere cheese, garlic and pancetta. He says it’s not bad. And even the mysterious and almost sacred mixing of eggs or just the yolks with cheese and pasta water ( to which I am devoted) is really a recent twist on a dish that has evolved thanks to Italian cooks on both sides of the Atlantic.

Another myth was cast aside in his chapter on tortellini – something that he insists is truly Bolognese in origin and not from Castelfranco or any other competing Emilia-Romagnan city (read Modena). The charming story that the inventor of the tortellino was inspired by the naval of Venus (and it sure looks like somebody’s belly button, if not hers) was fabricated in a poem written by an Italian engineer in 1908. This amateur poet’s name was Giuseppe Ceri and his clever little ditty became a pop hit so to speak and an integral part of the tortellini saga. Cesari includes an adroit translation of this very popular poem in his book:

Then to the great amazement

Of the innkeep at the door,

She shrugged off the bedclothes

As if she were quite alone,

And flung them to the floor,

Stretching out a lovely leg,

She rose from the ample bed

With a leap so indiscreet

That her gown happened to slip

Just a bit above the hip,

And that happiest of hosts

(Shall I be coy or honest?)

Espied the sacred navel of the goddess!

He ran quickly down the stairs;

Seizing the pasta freshly made

By his ancient kitchen maid

Who had rolled it on a board,

He took a tiny round,

Which he twisted all around

In a hundred different ways,

Trying hard to imitate

The holy navel’s special shape.

And so that squinter from Bologna,

Eying Venus’s bellybutton,

Learned the art of tortellini

To gladden every glutton!

One of the engaging aspects of his writing is that Cesari appreciates the changes that occur in these dishes that, like a nation’s language, evolve over time. And actually, these dishes when done correctly with good ingredients, are very simple and truly delicious, which is really their beauty. They do not need corporate embellishments such as the unfortunate amalgamations touted by the Olive Garden restaurant chain (chicken tortelloni Alfredo or ravioli carbonara, for example). Luca Cesari acknowledges innovation, while setting the record straight.

Kitchen Detail shares under the radar recipes, explores the art of cooking, the stories behind food, and the tools that bring it all together, while uncovering the social, political, and environmental truths that shape our culinary world.

The Venus navel poem is very clever. Thank you for giving a small cut to Olive Garden. I was once asked what they could do to improve the menu. I answered “Serve Italian food.”

Cuisines are modified by good cooks and bad. My Irish Grandmother’s best casserole was an Eastern European dish taught to her by her German friend from school. My Mom made it more Italian. She was not Italian, but a cook who explored food.

Hello Catherine,

I had to look up other Olive Garden menu iterations after you wrote this comment. They are often too weird to be believed. Would love to know this casserole recipe too!

Nancy