Read Time: 5 Minutes Subscribe & Share

Homecoming

Covid restrictions come in different colors here in Italy. Yellow is mild, orange is medium and red is high. White is without any restrictions at all, but it’s so unlikely that the Ministry of Health only mentions it as a side note in its official classification. Ever since the color code system’s implementation, we’ve been living in a changing mosaic of regions in one of these three hues.

Covid restrictions come in different colors here in Italy. Yellow is mild, orange is medium and red is high. White is without any restrictions at all, but it’s so unlikely that the Ministry of Health only mentions it as a side note in its official classification. Ever since the color code system’s implementation, we’ve been living in a changing mosaic of regions in one of these three hues.

During the second coronavirus wave, Emilia Romagna, the region I live in, became orange on November 15 of last year, which meant that restaurants and cafés could no longer provide on-premises service and museums had to close their doors to the public. Tangible culture and art history are a determining factor of the quality of life in Italy – I mean why else are so many people hankering to vacation here. When access to these everyday places of beauty is shut down, it feels like you’ve lost a source of nourishment.

Even though only two months passed before Emilia Romagna became yellow again on January 15, I felt starved for seeing something beautiful made by humans. Something that reveals something about our past in a physical space and not just on my computer screen. The first trip on my Covid bucket list was Riscoperta di un capolavoro (Rediscovery of a Masterpiece), a show at Palazzo Fava temporarily reuniting an Italian Renaissance altarpiece known as the Griffoni Polyptych. Although still weary of changing our habits of limited excursions and avoiding closed public spaces, my son and I donned our masks like superheroes and dashed off to see a very special homecoming.

Piecing Together A Renaissance Mystery

Francesco del Cossa and Ercole de’ Roberti painted the panels of this altarpiece around 1472-1473 for the Griffoni family’s chapel in San Petronio, Bologna’s main church in Piazza Maggiore. When the chapel became the property of the Aldrovandi family three centuries later, Cardinal Pompeo Aldrovandi had the polyptych dismantled and removed in order to renovate the space with contemporary artwork and furnishings. What had been a celebrated image in the city’s most popular church vanished overnight, not to be seen again by the local population for nearly three hundred years.

Bologna’s main church in Piazza Maggiore. When the chapel became the property of the Aldrovandi family three centuries later, Cardinal Pompeo Aldrovandi had the polyptych dismantled and removed in order to renovate the space with contemporary artwork and furnishings. What had been a celebrated image in the city’s most popular church vanished overnight, not to be seen again by the local population for nearly three hundred years.

Piece by piece, the Griffoni polyptych was sold to families and later to museums and private collections via antique markets in the nineteenth century. Divvied among Italy, France, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and the United States, it became almost impossible to imagine the original altarpiece with visual access to just one panel.

Yet many have. The most successful sleuth was art historian Roberto Longhi, who reconstructed Cossa and Roberti’s masterpiece in his 1935 essay on artists from Ferrara Officina ferrarese. Eighty-five years after this landmark work, the museum organization in Bologna Genus Bononiae Musei nella Città united together the disparate panels in a single exhibition under the coffered ceilings of Palazzo Fava.

The occasion was just as historical as the effort behind it was monumental: three years of negotiation and design, the labor of one hundred people and loans from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, National Gallery of London, the Louvre, Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan, Cagnola Collection of Gazzada, Vatican Museums, Pinacoteca Nazionale di Ferrara, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen of Rotterdam, Vittorio Cini Collection of Venice.

Look Into My Eyes

The polyptych’s remaining sixteen panels center around the life of Saint Vincent of Ferrer. Canonized in 1455, the Dominican priest stands above a tableau of his miracles and is surrounded by other religious celebrities, with paintings of the crucifixion and the annunciation hovering over them all.

tableau of his miracles and is surrounded by other religious celebrities, with paintings of the crucifixion and the annunciation hovering over them all.

Saint Vincent might be the central figure, but the real showstopper is Saint Lucy.

Most people remember Saint Lucy because she is often depicted holding her eyes on a plate or in a cup. Supposedly executed after an upset suitor accused her of being a Christian at a time when the growing religious community was being persecuted, Lucy’s story was embellished in the Middle Ages with her eyes being gouged out before her death. Her name means “light” and early on Saint Lucy was venerated as a protector of sight, so the loss of her eyes must have seemed a fitting emblem of her martyrdom.

In the Griffoni Polyptych, Saint Lucy is emblazoned against a gold background with harmonious colors, a graceful pose and magnificent fabric. However, the most compelling and original detail is how she holds her eyes like two buds on a single stem. This elegant and surreal gesture draws you into her hypnotic world and the imaginative aesthetic of the Renaissance. The painting seems as powerful now as it did when I saw it as a child at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

Saint Sebastian

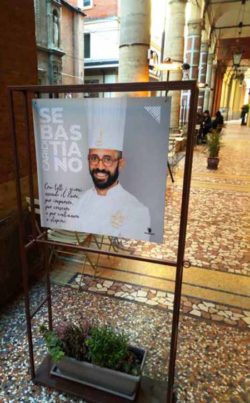

Arrow-decorated Saint Sebastian is not one of the saints represented in the Griffoni Polyptych, but is the pastry chef Sebastiano Caridi at the museum’s Caffè Letterario and something of a local icon. Large pictures of him line the streets around Palazzo Fava. One of those giant images grabbed the attention of our son back in 2019 when Caridi inaugurated the new pastry shop. When Gregorio understood that the beautiful mignons and vibrant cakes in the window were the handiwork of the man he had seen in the picture, he insisted on meeting the pasticciere from Calabria in person. My husband and son waltzed through the towering glass doors of pasticceria

Arrow-decorated Saint Sebastian is not one of the saints represented in the Griffoni Polyptych, but is the pastry chef Sebastiano Caridi at the museum’s Caffè Letterario and something of a local icon. Large pictures of him line the streets around Palazzo Fava. One of those giant images grabbed the attention of our son back in 2019 when Caridi inaugurated the new pastry shop. When Gregorio understood that the beautiful mignons and vibrant cakes in the window were the handiwork of the man he had seen in the picture, he insisted on meeting the pasticciere from Calabria in person. My husband and son waltzed through the towering glass doors of pasticceria and my son’s wish was greeted with a miraculous discovery. Sebastiano just happened to be taking a break and was free. Seeing and introducing himself to the person in the larger than life photos was for Gregorio, in his own words, “The best day of my life.”

and my son’s wish was greeted with a miraculous discovery. Sebastiano just happened to be taking a break and was free. Seeing and introducing himself to the person in the larger than life photos was for Gregorio, in his own words, “The best day of my life.”

The promise of a treat at Sebastiano’s post-exhibition sparked Greg’s enthusiasm about seeing the show, as did the audio guide created just for kids. We floated from the bookshop into the frescoed ceiling café. Its pastel, cozy interior makes you want to sit down and relax. The colorful and pristinely displayed pastries make you want to eat with your eyes and your mouth. We didn’t choose anything fancy, just a plain cornetto and some savory mignons. But when orange juice is served to a child in a stemmed wine glass, even minor moments can feel like a grand occasion. And this grand occasion gave me hope that one day soon, we’ll see code white.

The promise of a treat at Sebastiano’s post-exhibition sparked Greg’s enthusiasm about seeing the show, as did the audio guide created just for kids. We floated from the bookshop into the frescoed ceiling café. Its pastel, cozy interior makes you want to sit down and relax. The colorful and pristinely displayed pastries make you want to eat with your eyes and your mouth. We didn’t choose anything fancy, just a plain cornetto and some savory mignons. But when orange juice is served to a child in a stemmed wine glass, even minor moments can feel like a grand occasion. And this grand occasion gave me hope that one day soon, we’ll see code white.

Juggling nuance between Italian and English, Tatiana lights up her five-burner kitchen top with nostalgia for American food, Bologna-inspired fare and cross-cultural inventions. She and her husband endlessly debate on cooking with or without a recipe. Their son just hopes that dinner will either be plain or have chocolate in it.

Comments are closed here.

Follow this link to create a Kitchen Detail account so that you can leave comments!